2010 MIT

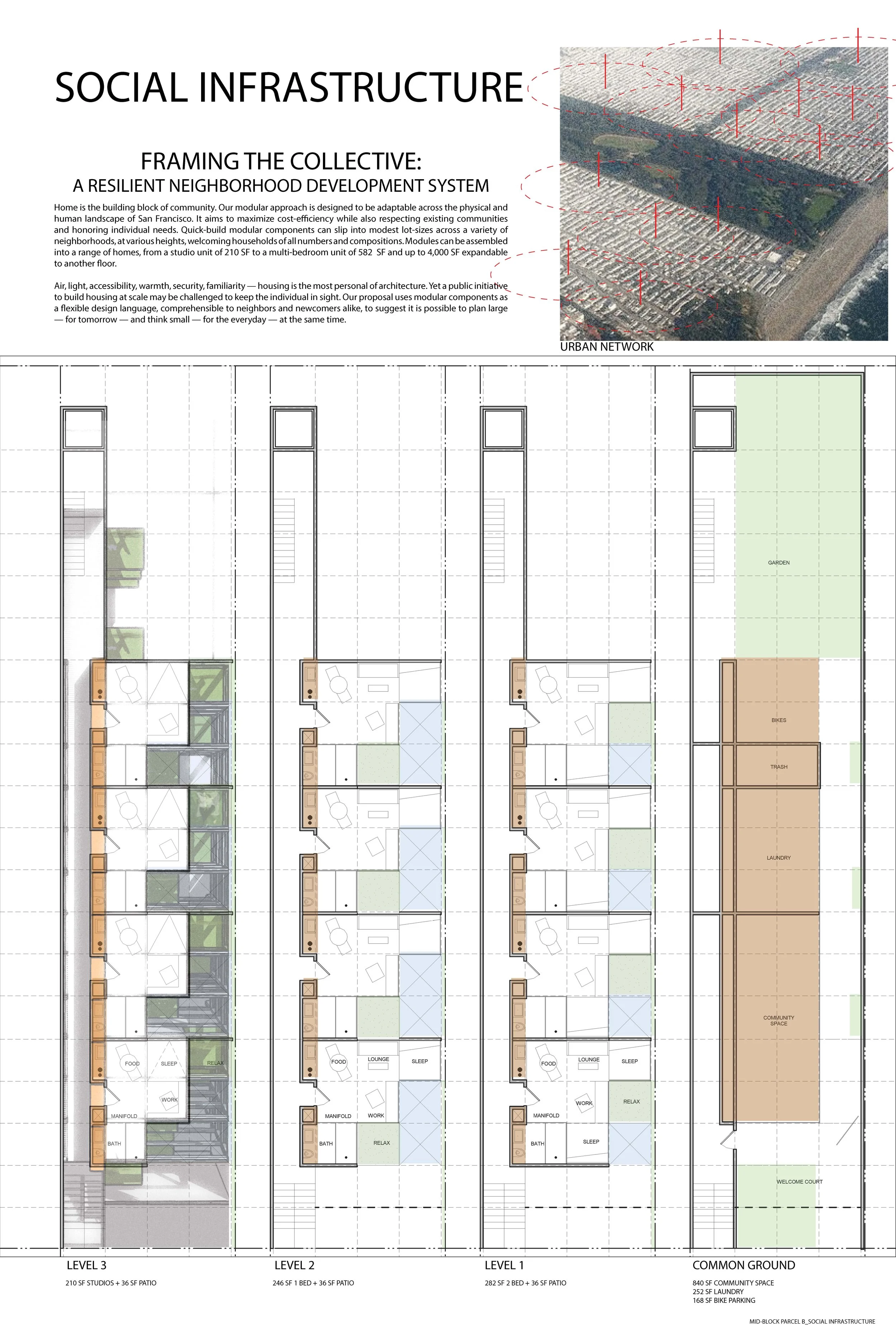

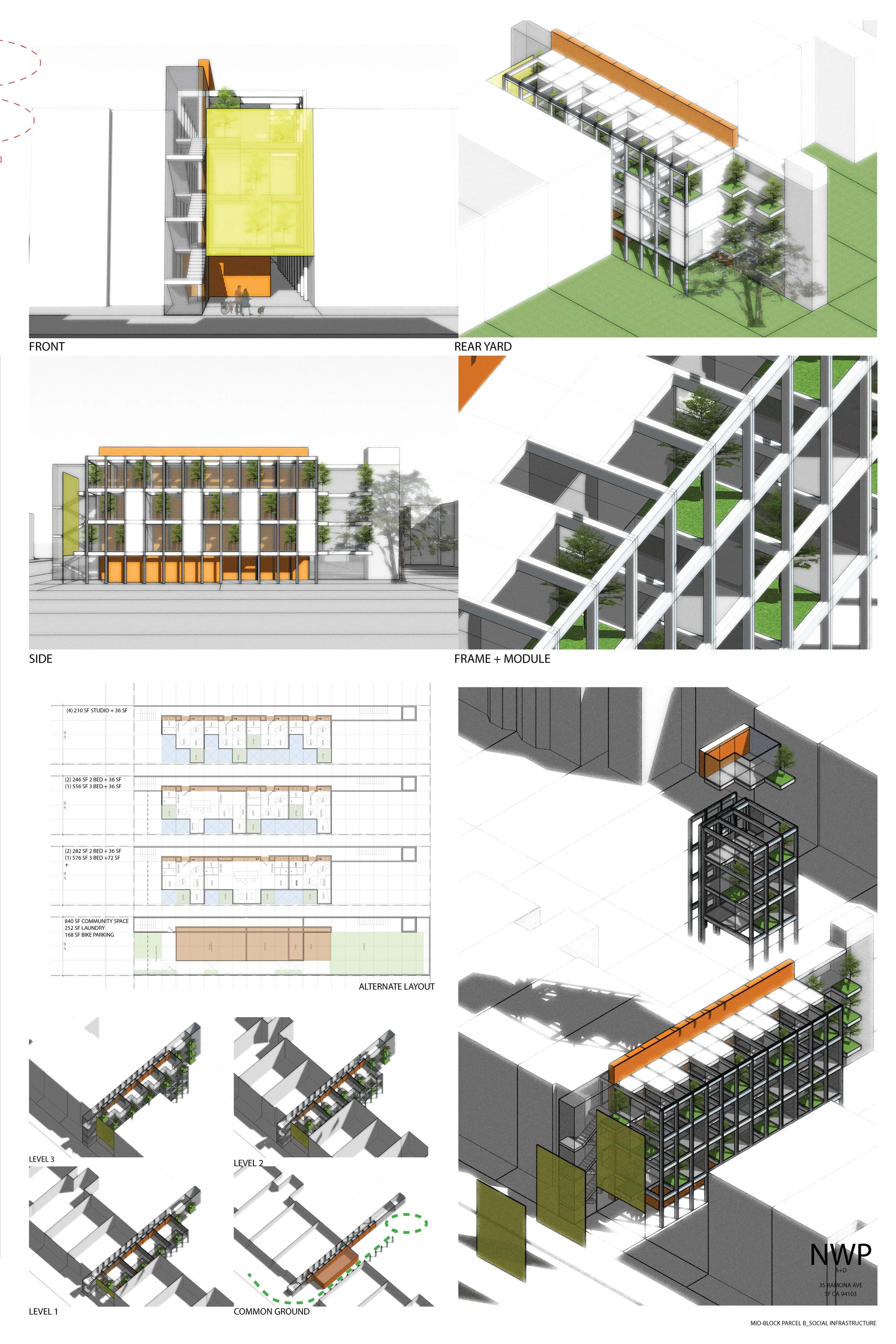

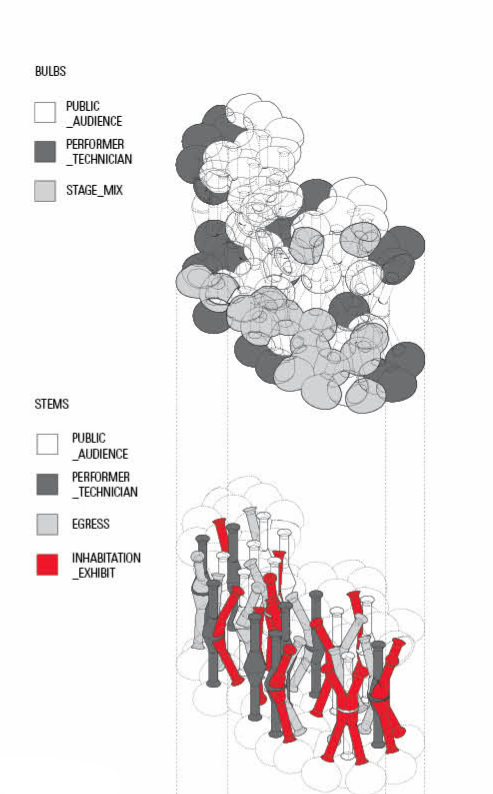

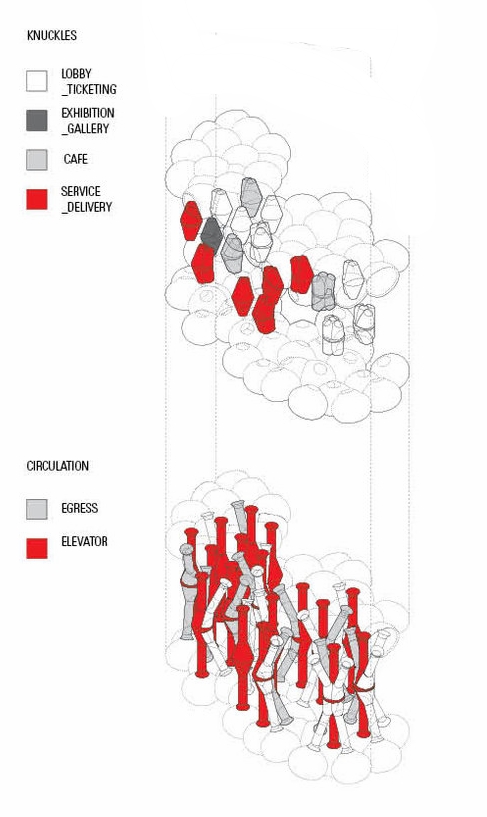

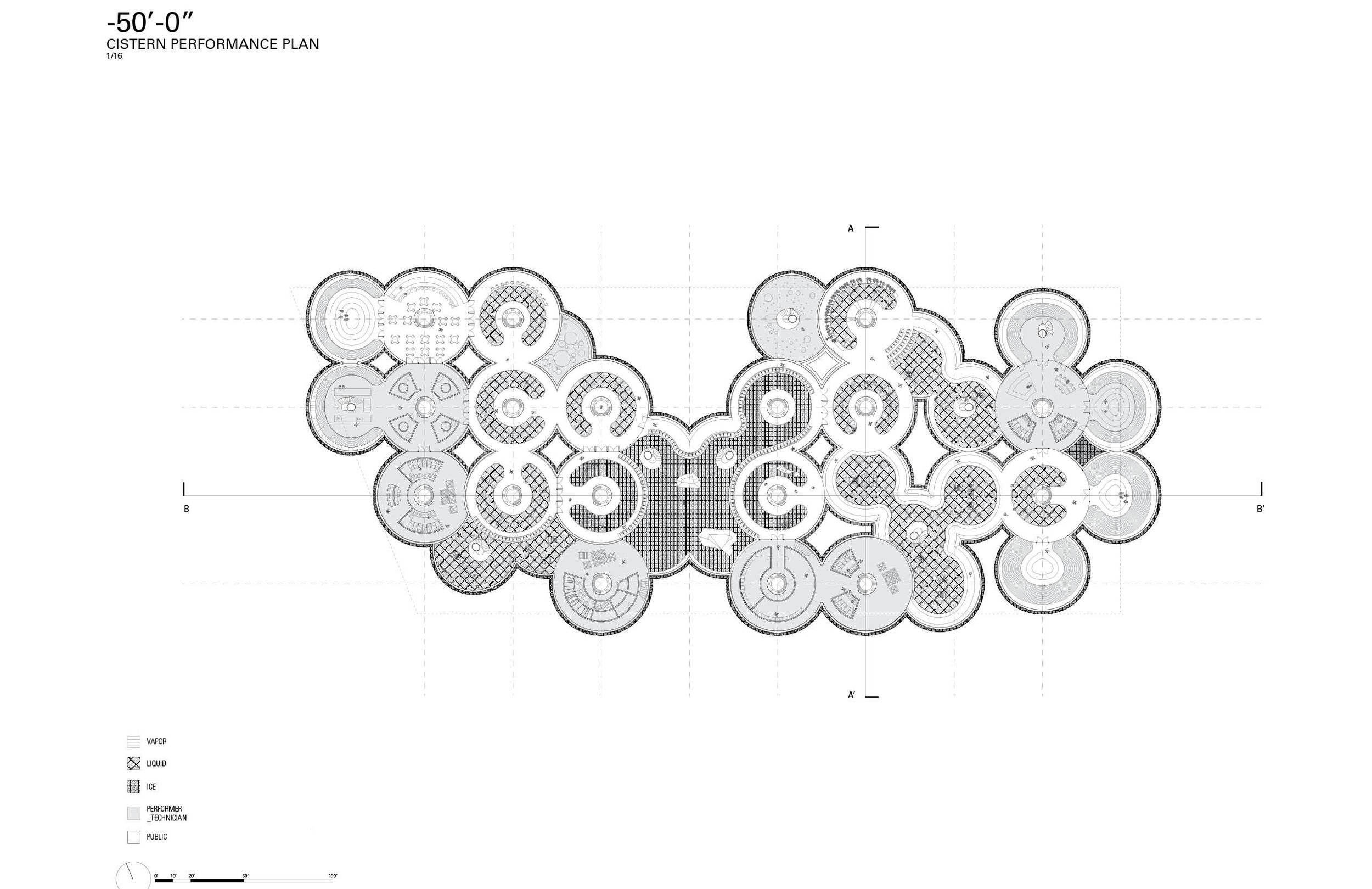

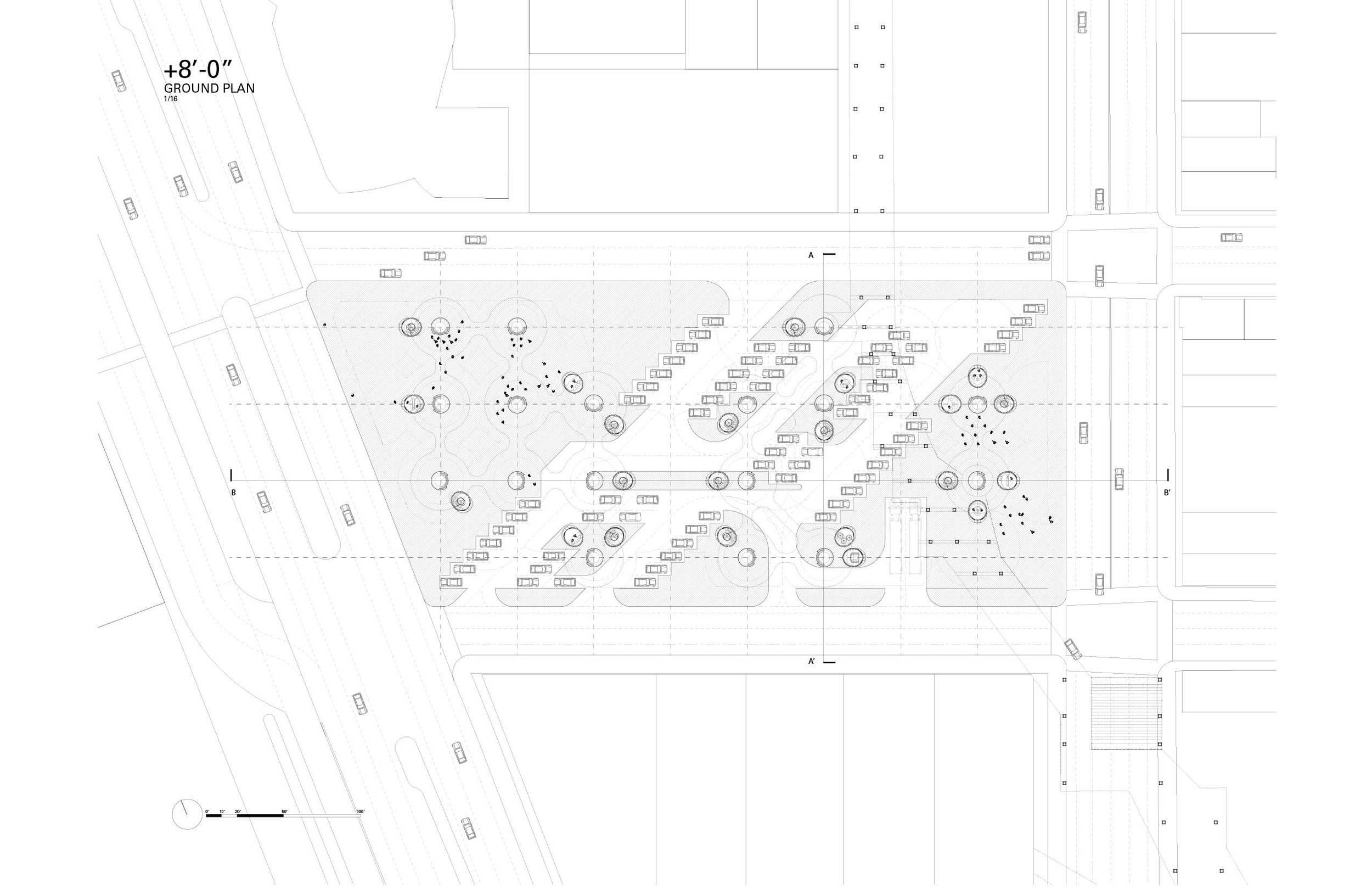

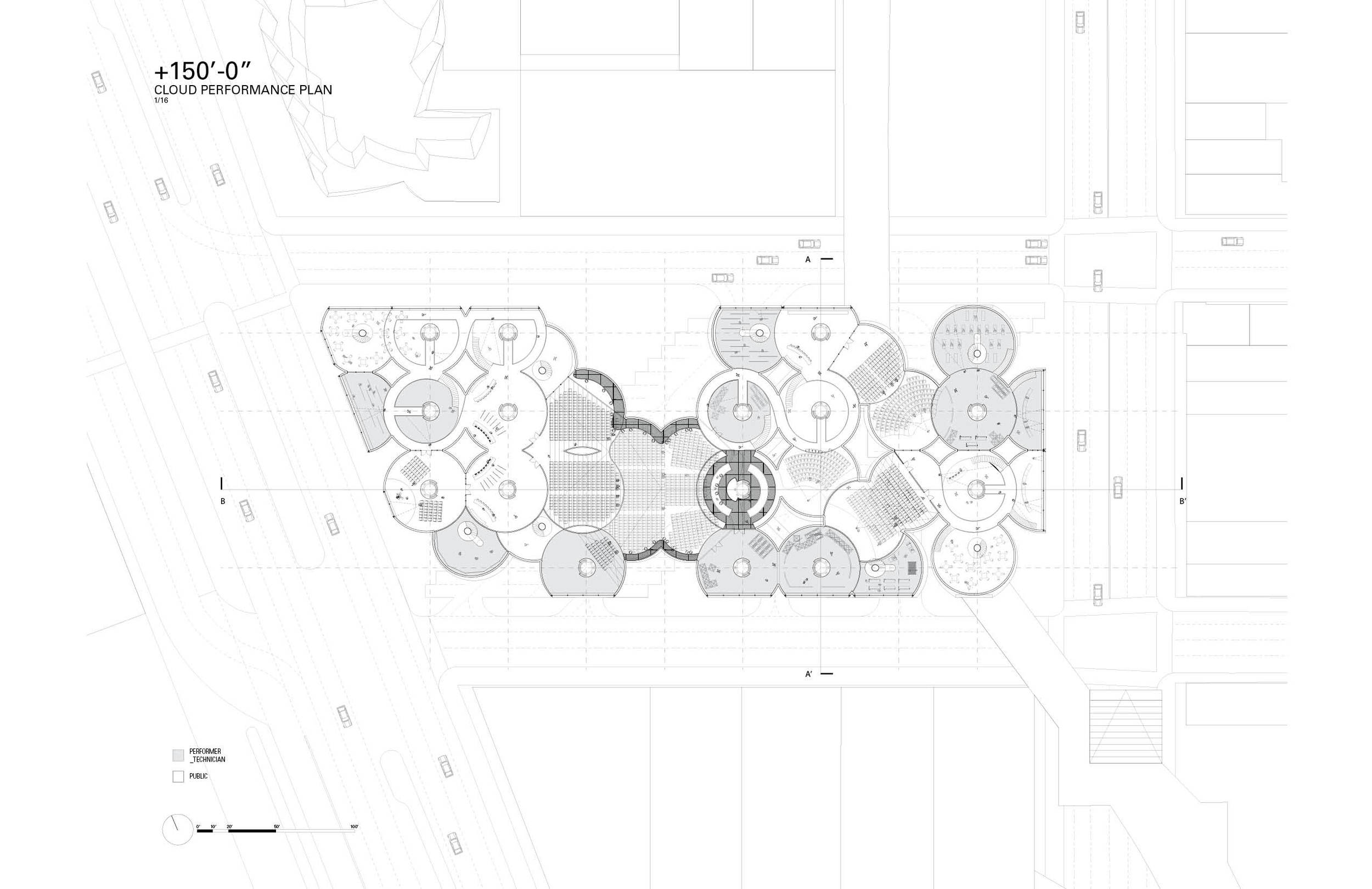

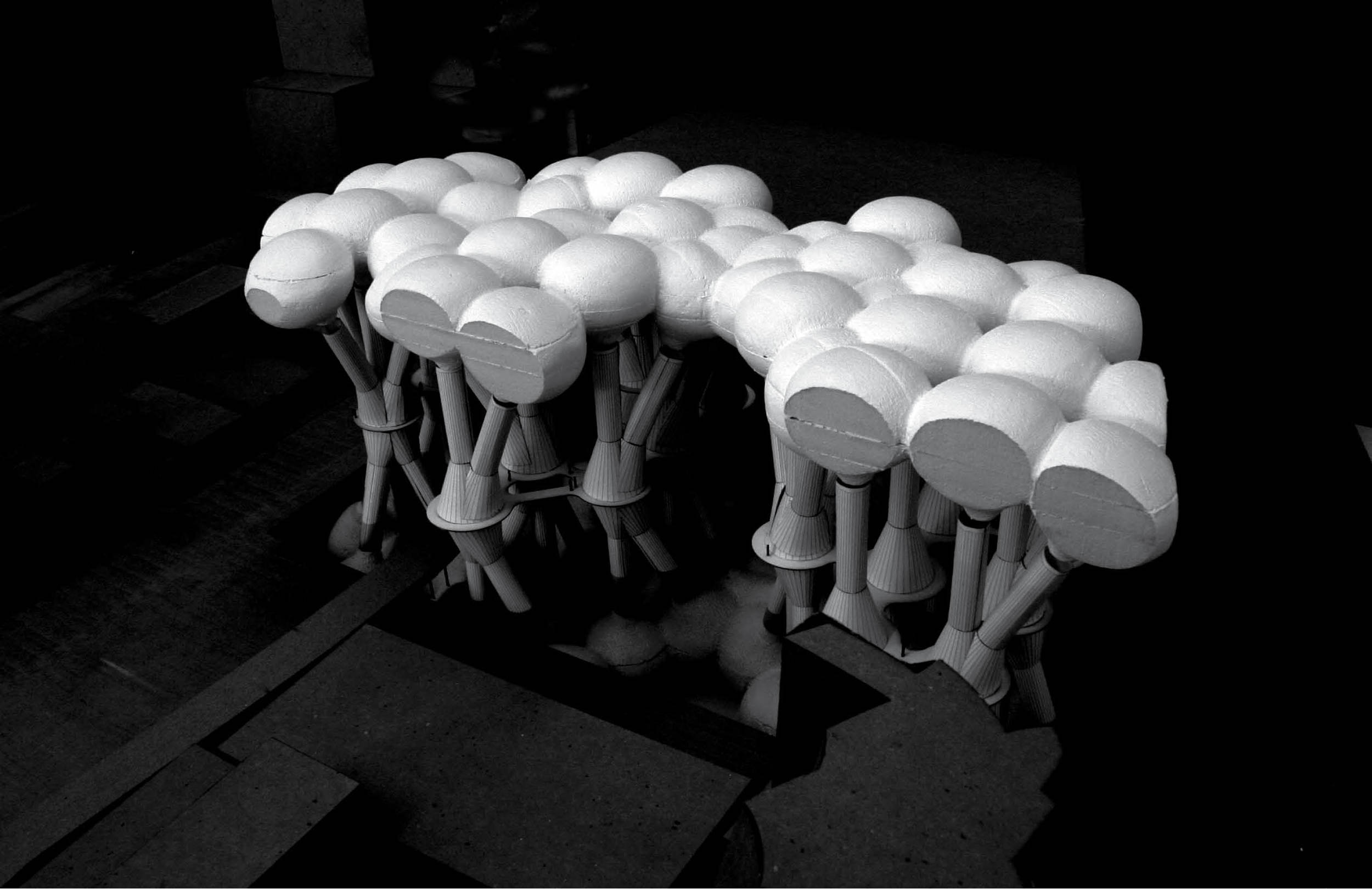

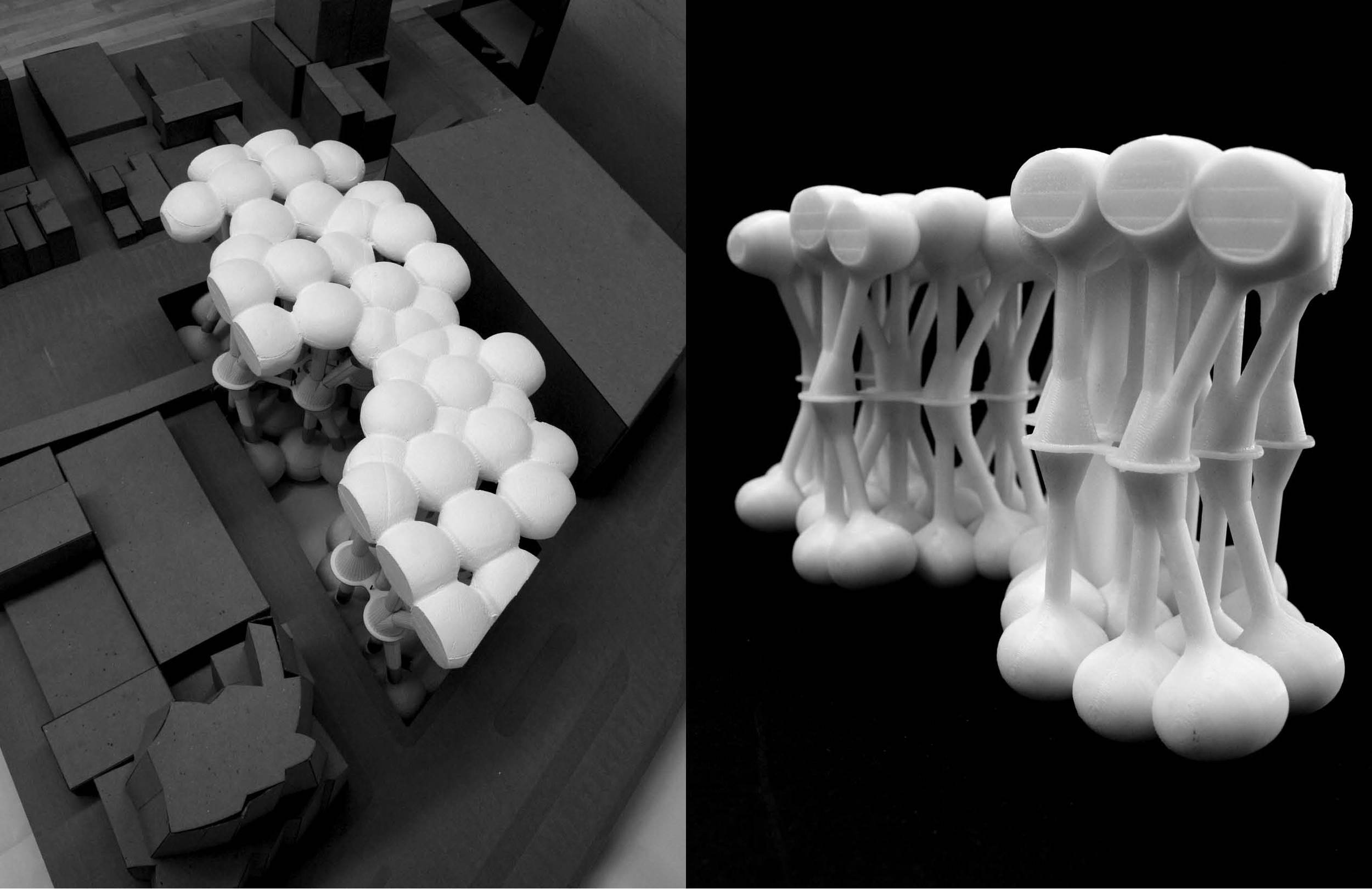

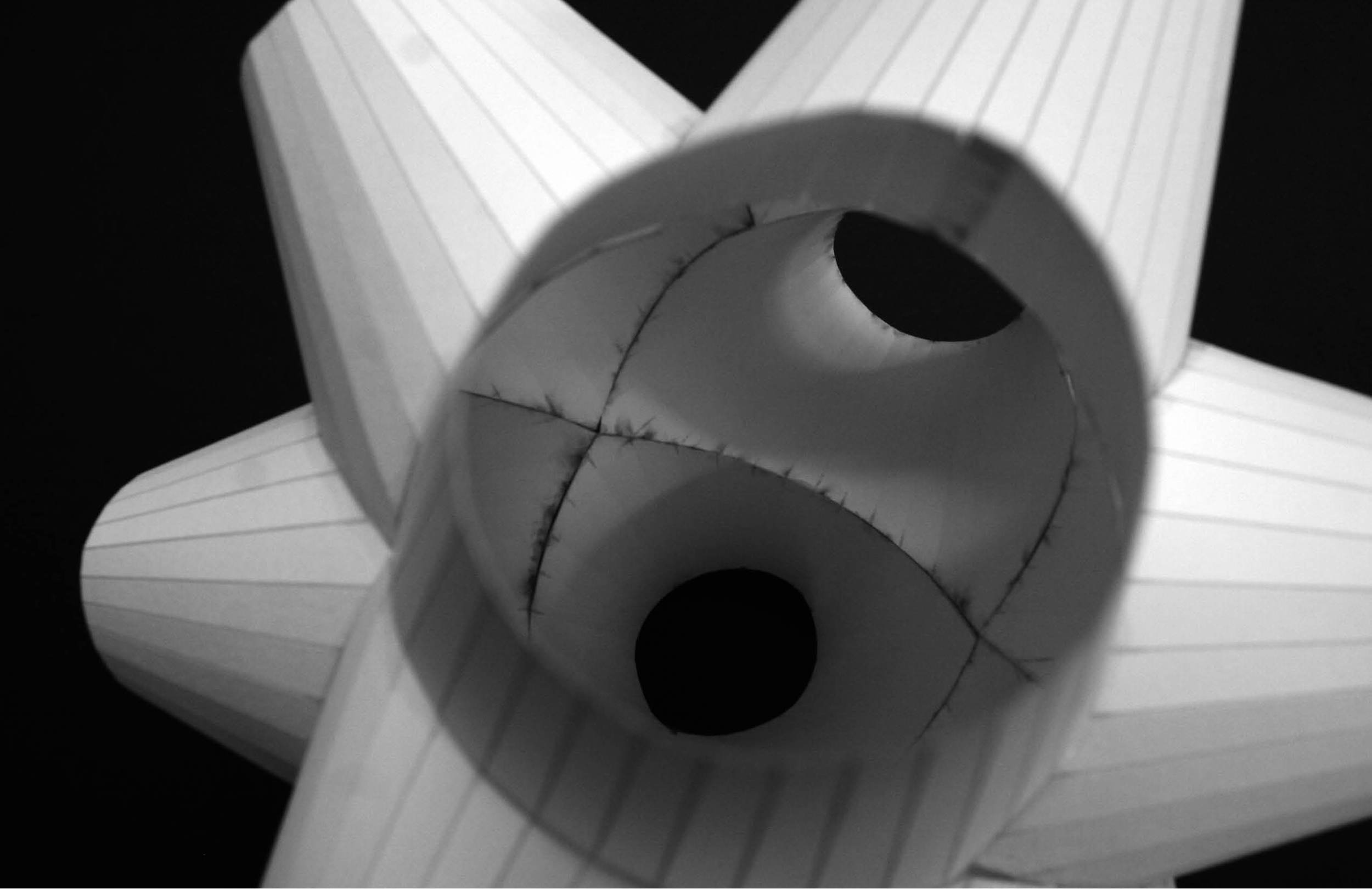

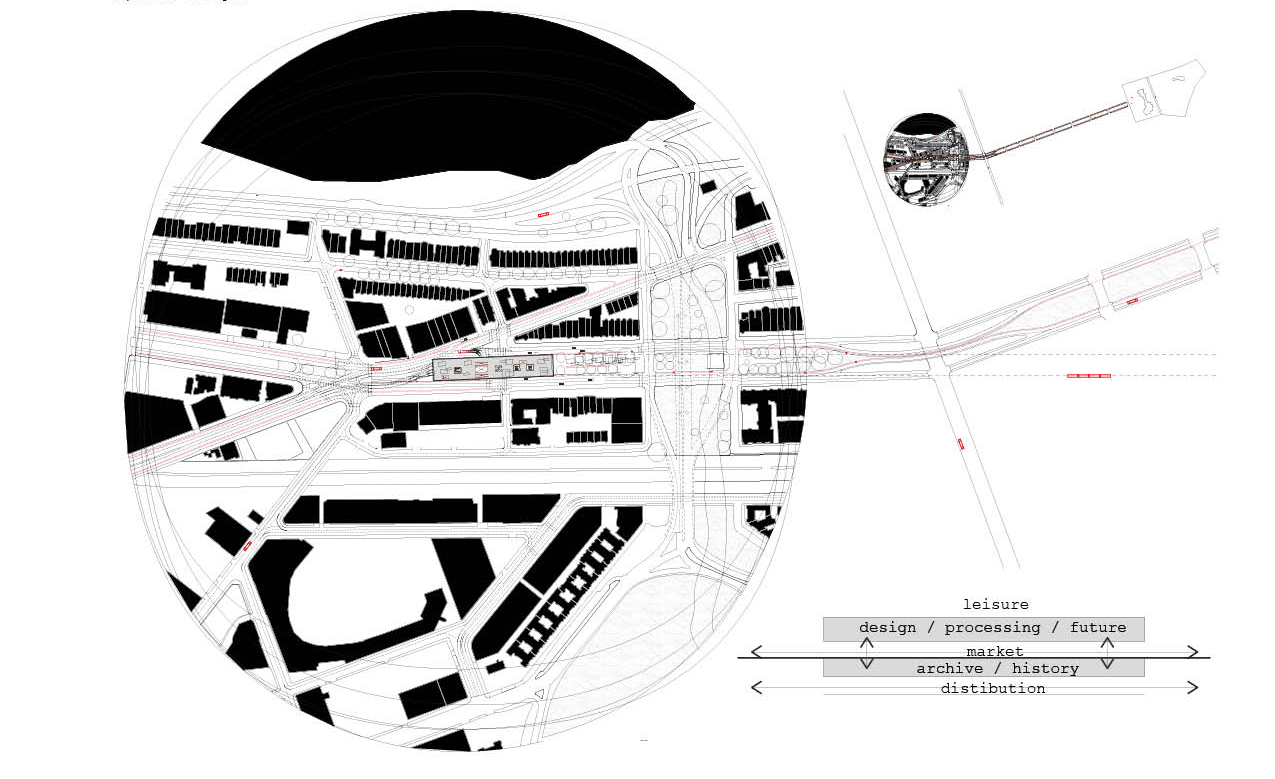

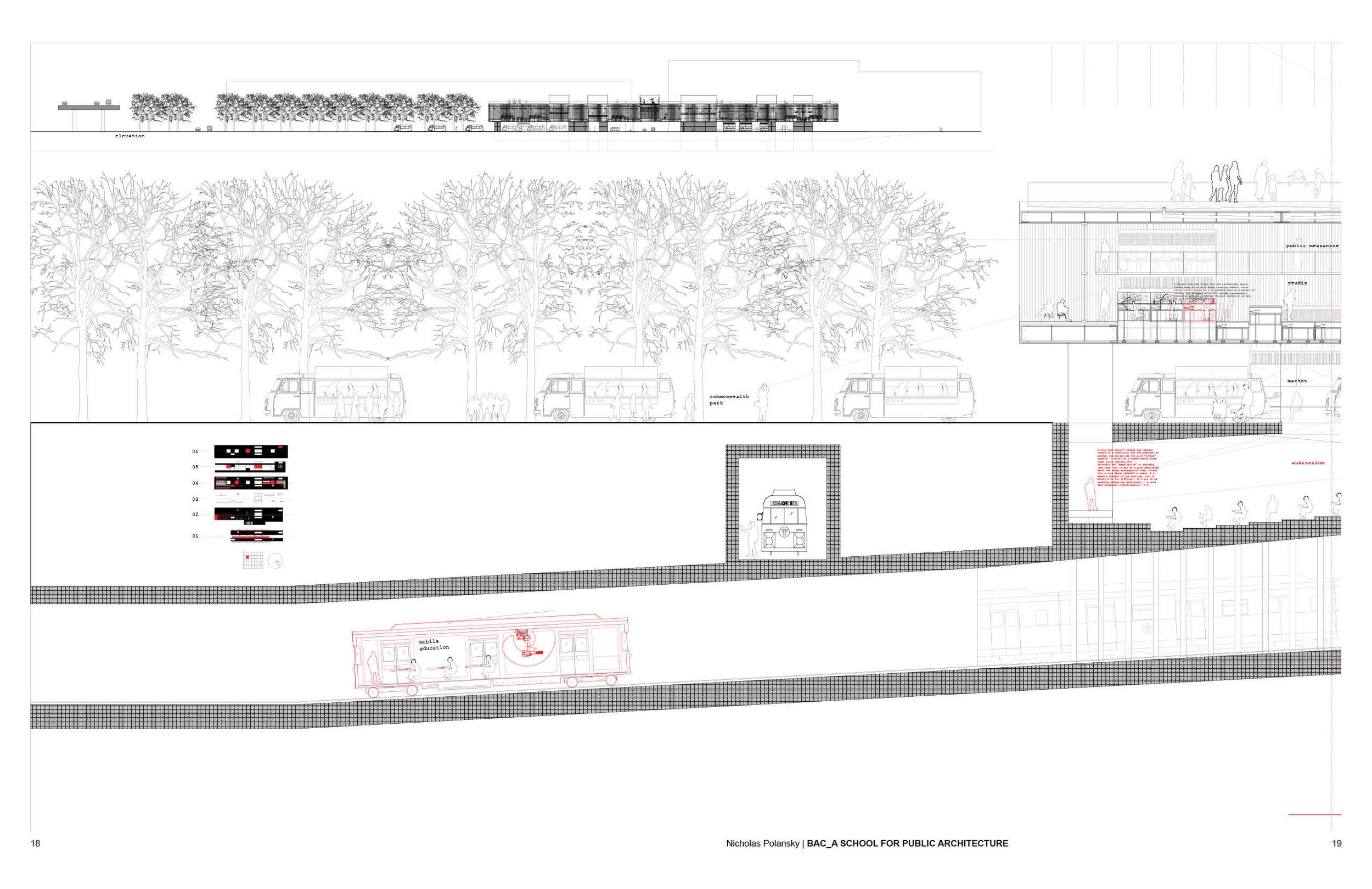

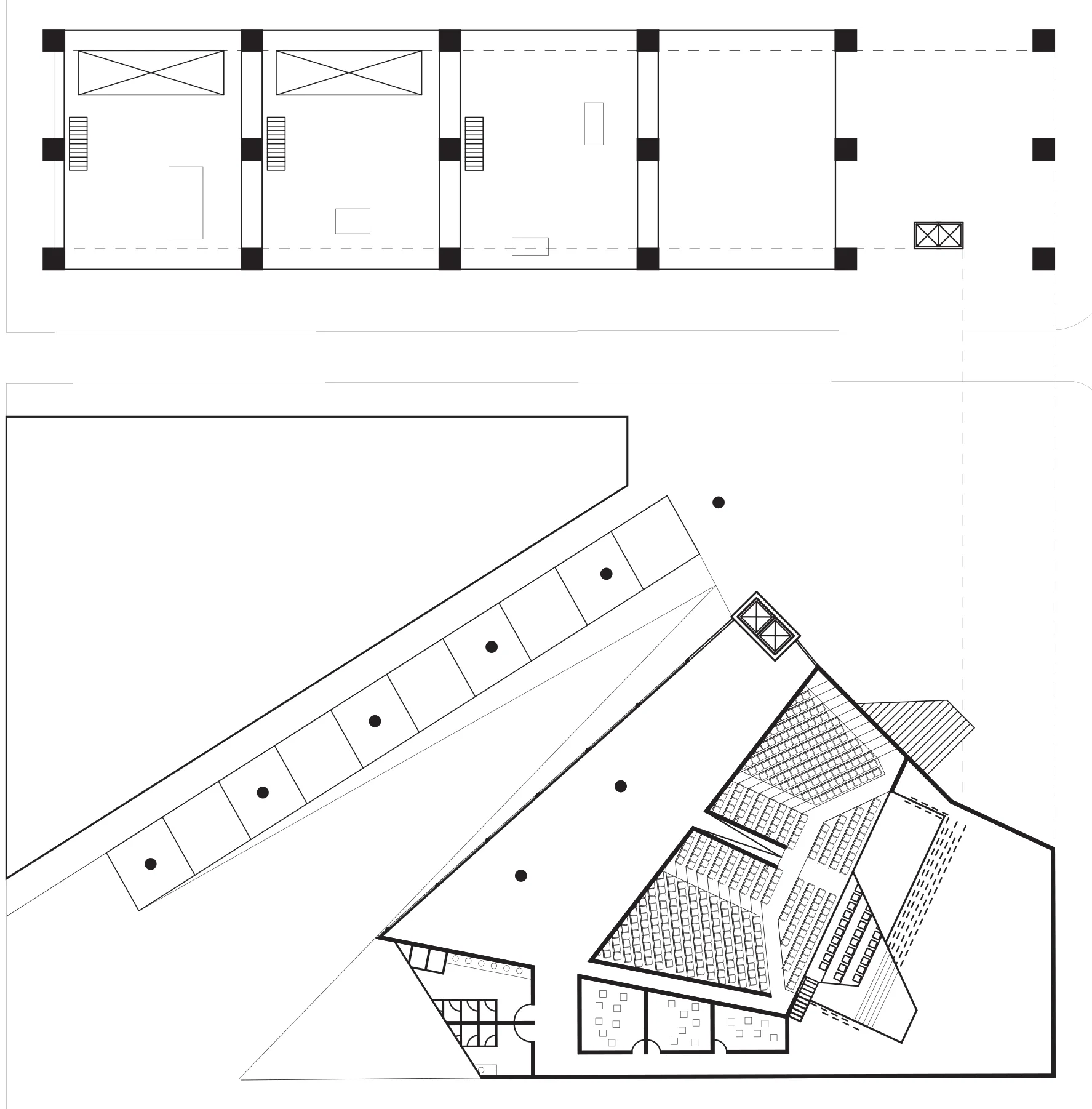

This project is an attempt to re-conceptualize the purpose of a Design Institute in collaboration with Kenmore station and its impact as a cultural, technical, and scientific agent in the immediate urban context of Boston. It is intended to work like an organism. By working through the act of design, from conception, through review, technical experiment, execution, and finally publication, and archive. This loop of production drives the organization of the building through a hierarchy of mechanisms designed to move people, material, and data and multiple scales.

At the smallest scale, and idea is exchanged between two people. At the largest scale, an idea is exchanged between the institute and the city. By directly engaging the pulse of the city, this school for architecture can directly curate its curriculum to begin to identify and solve real problems.

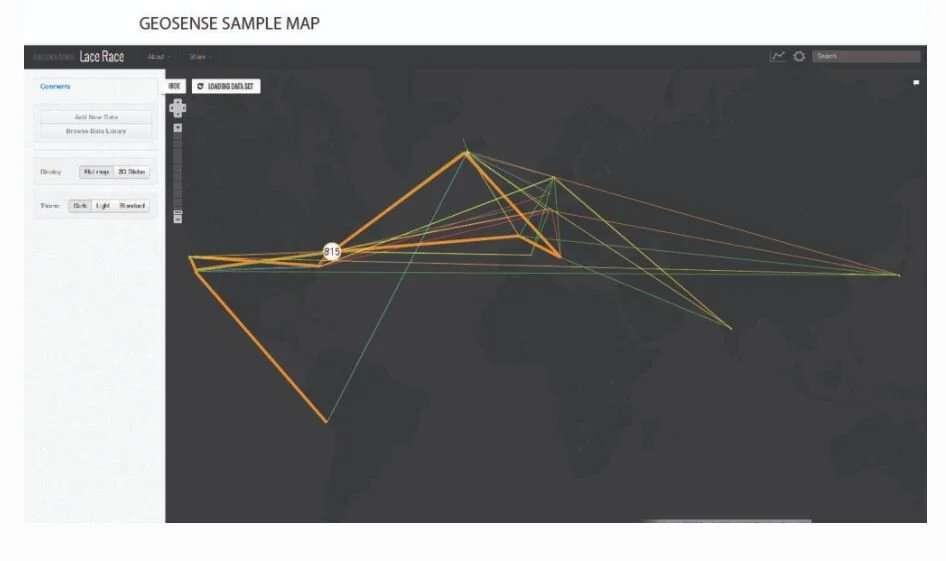

The product of the school is centered around the production of the collective archive. Each partition is dedicated to cluster of personal work spaces and managed by a specialist. The specialist guides the group through SEARCH practices, mapping demographic, natural, ecological, economical, and political aspects of a particular issue until a clear problem is defined. At various phases of this process, peer, and public review is invited or imposed for proper feedback through the process for design intervention.

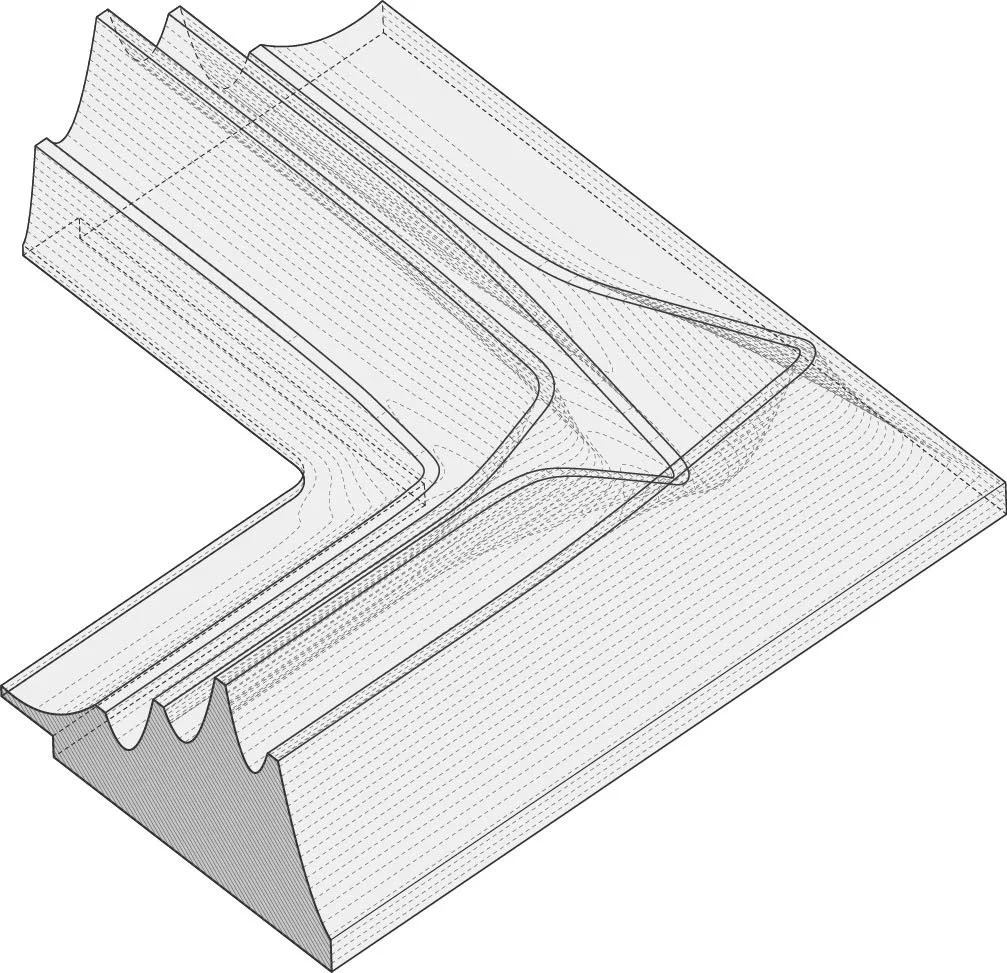

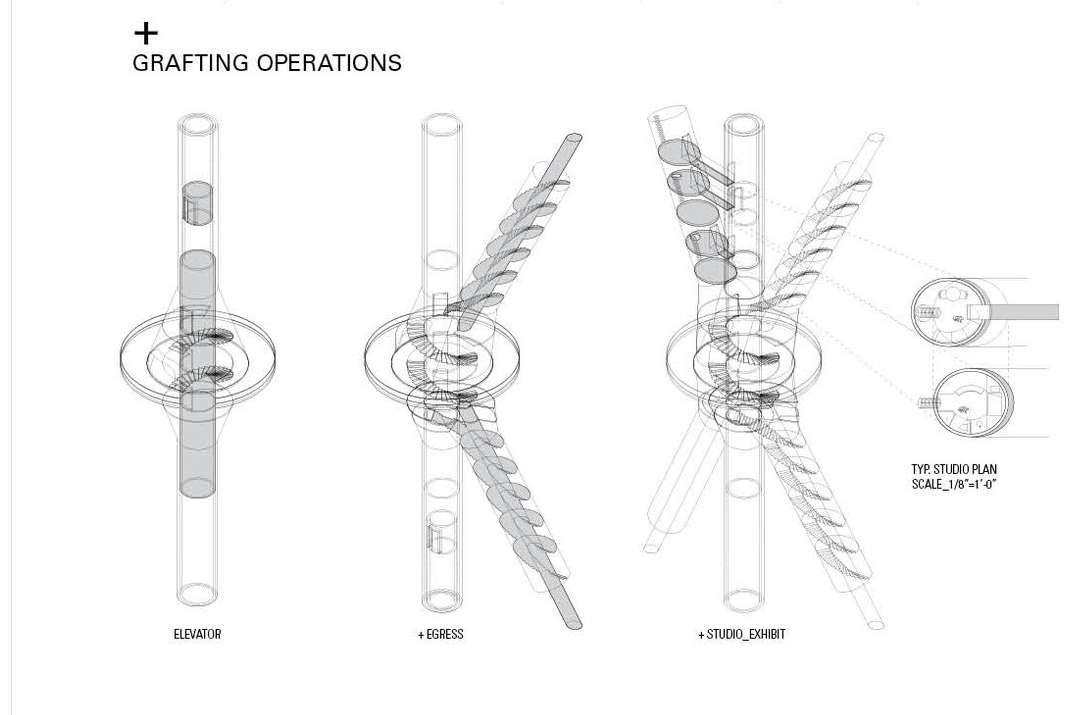

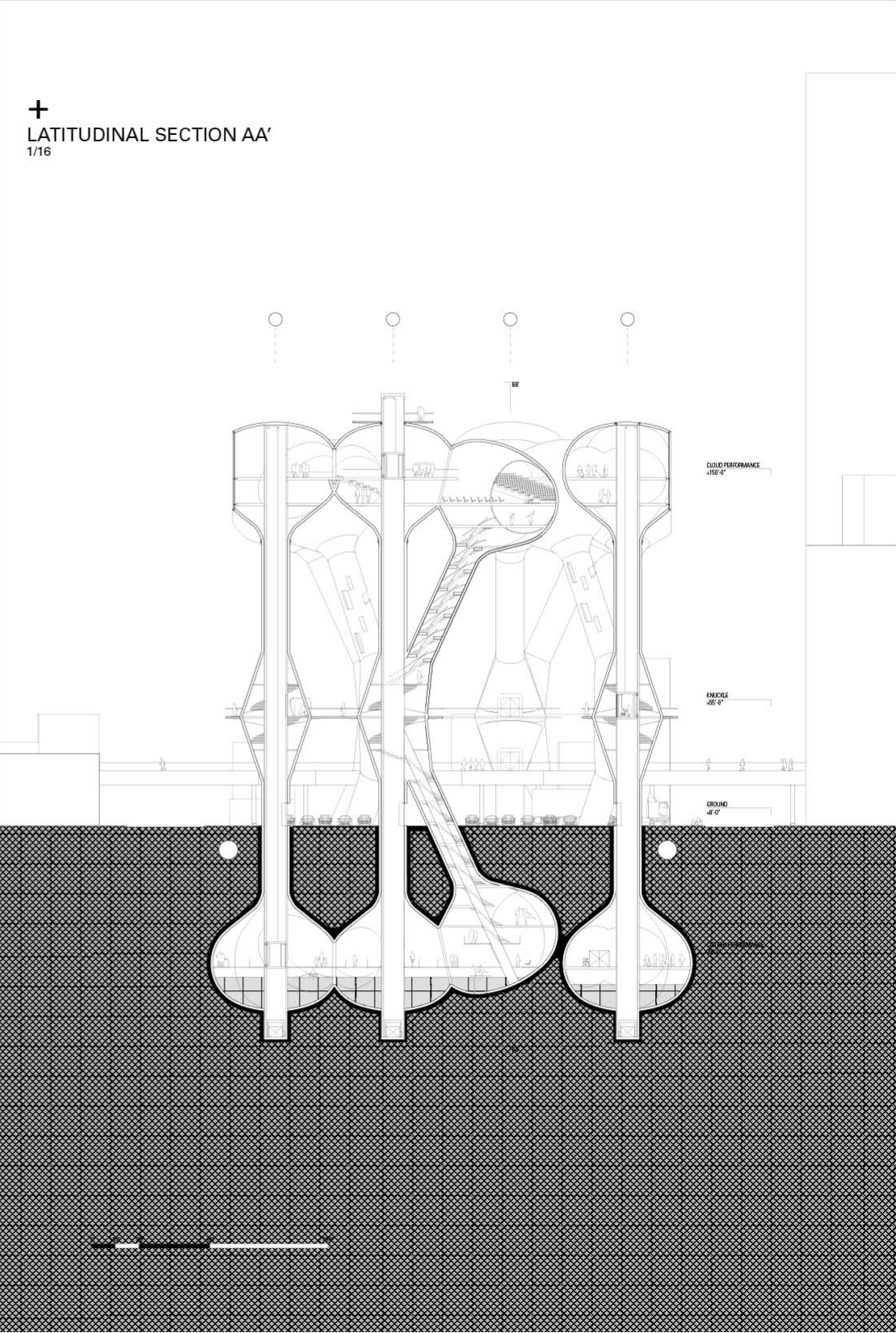

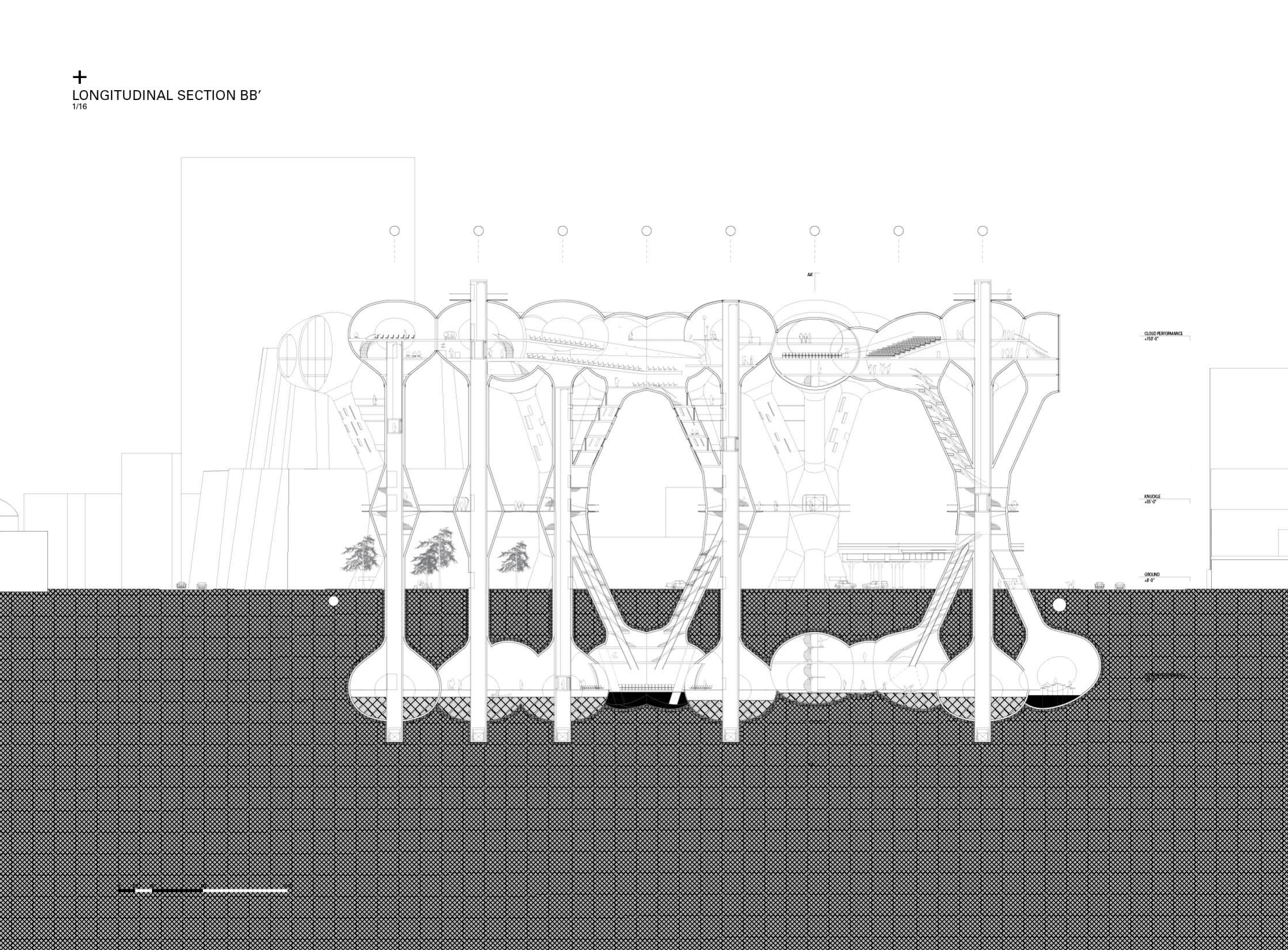

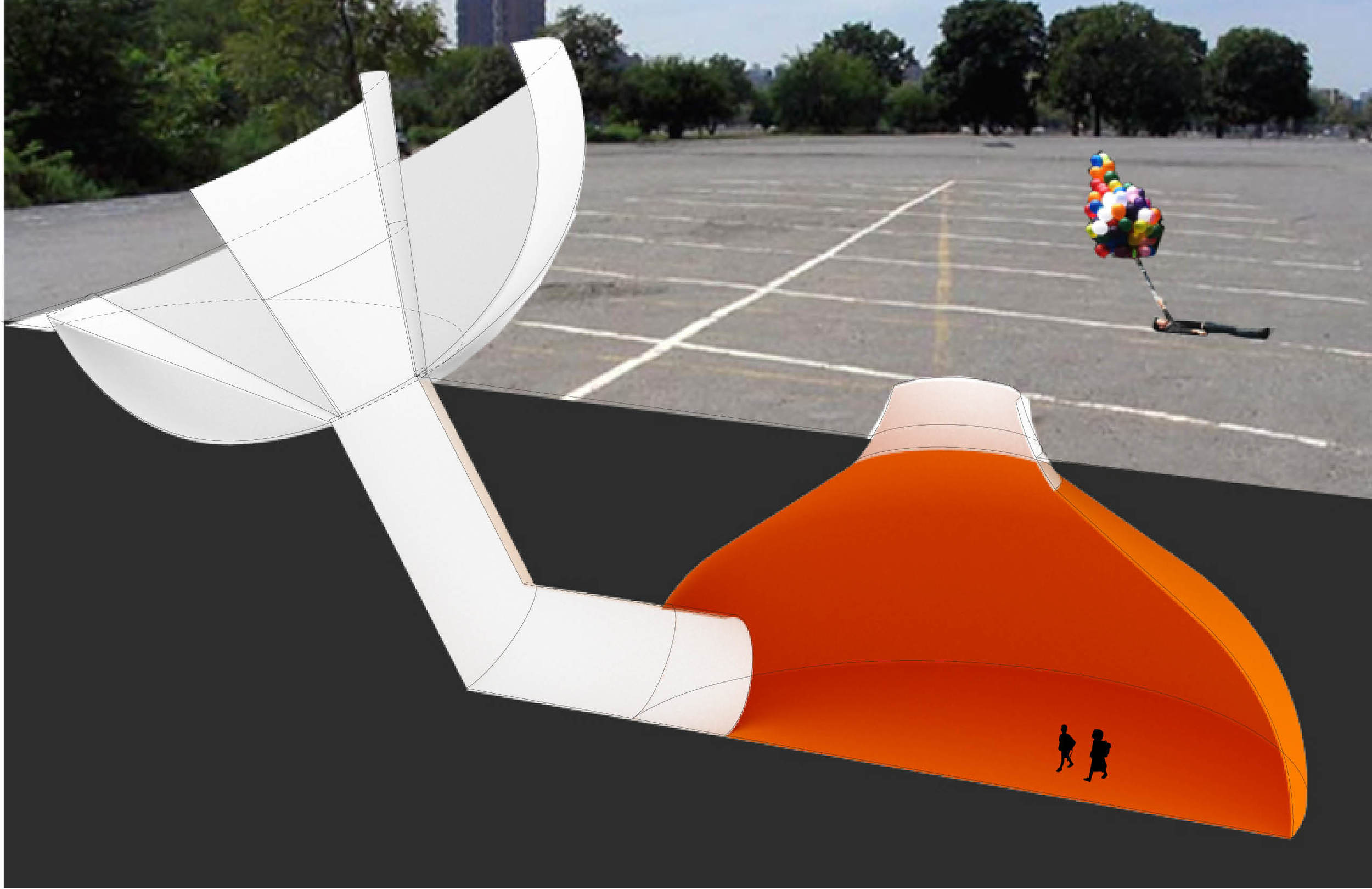

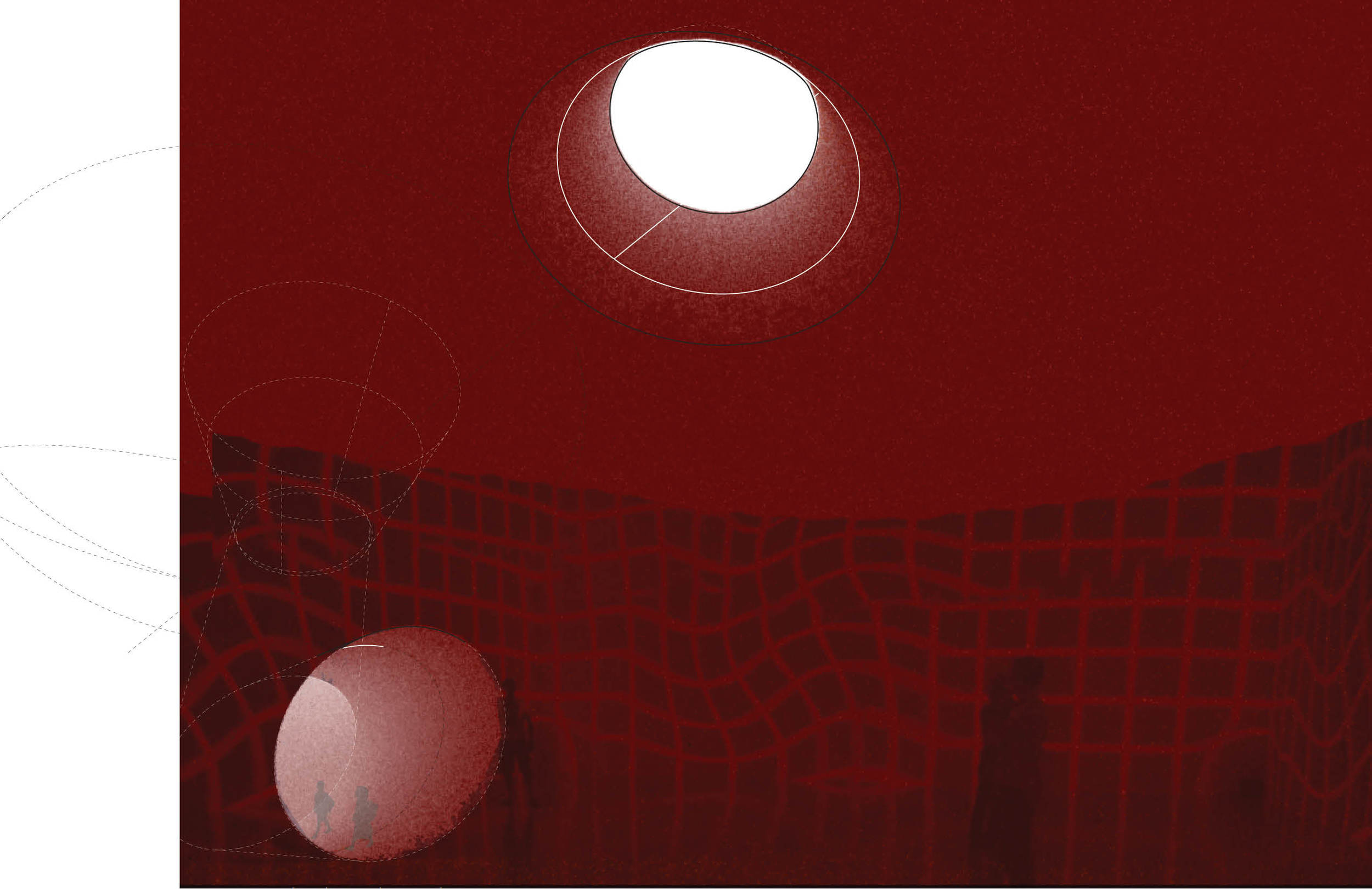

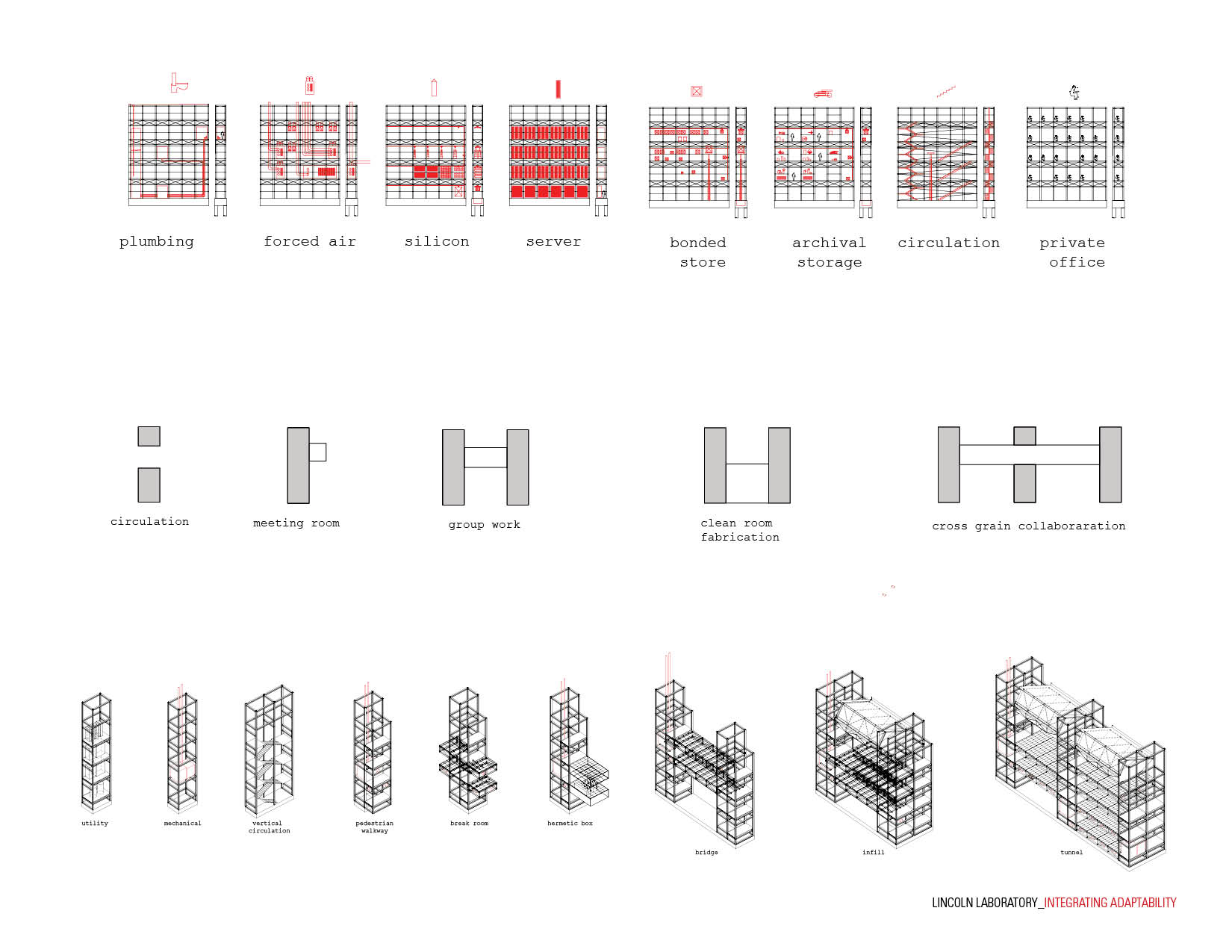

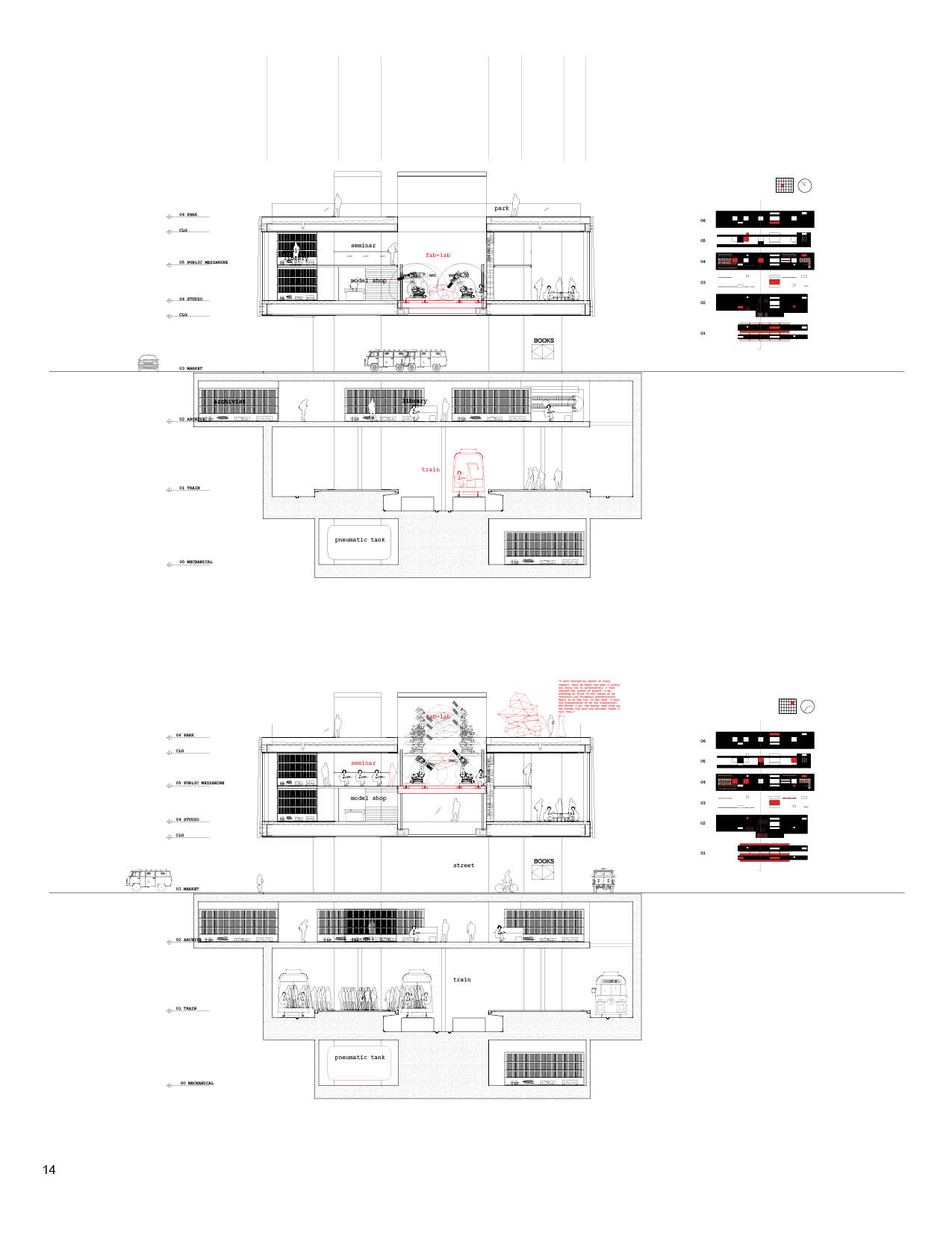

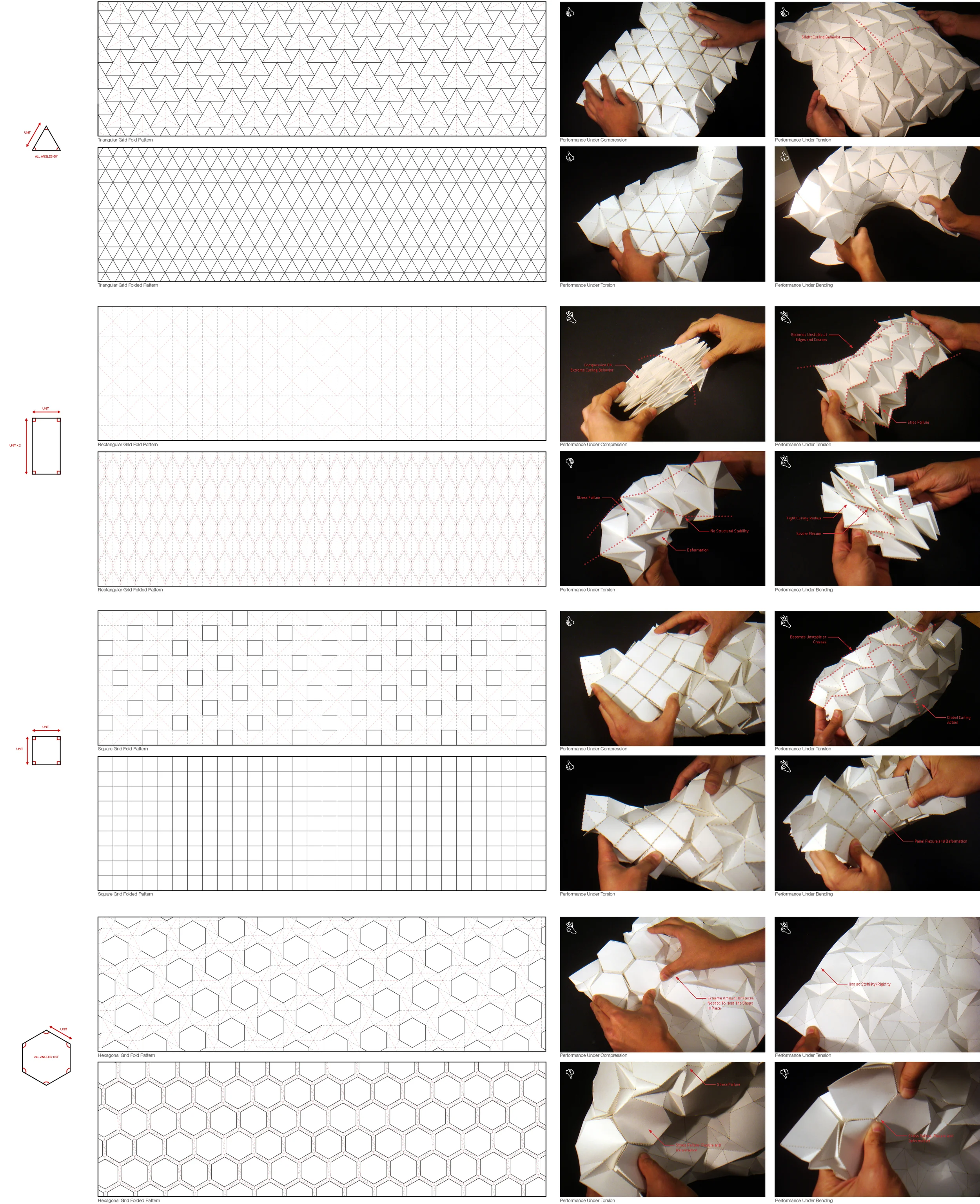

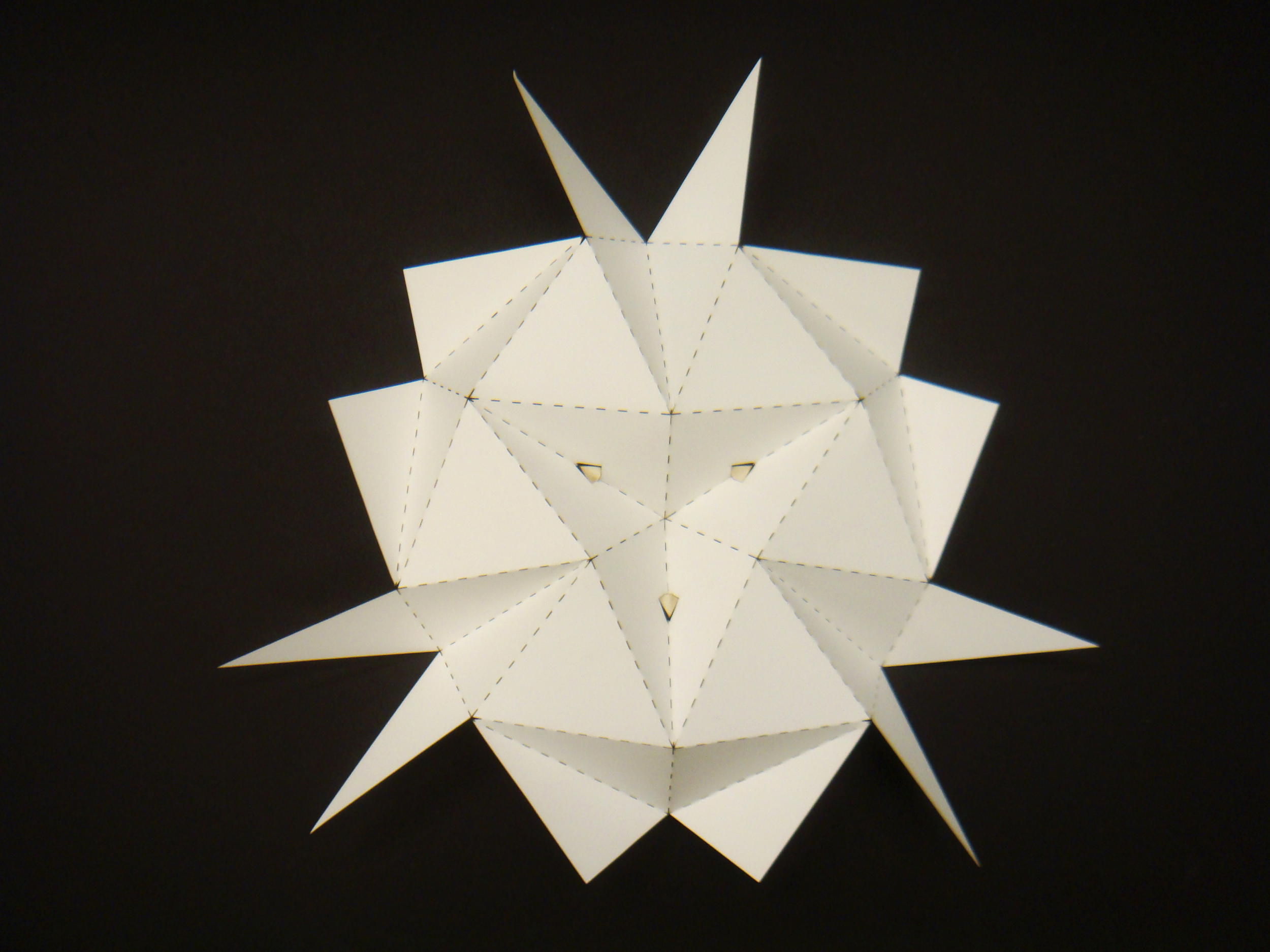

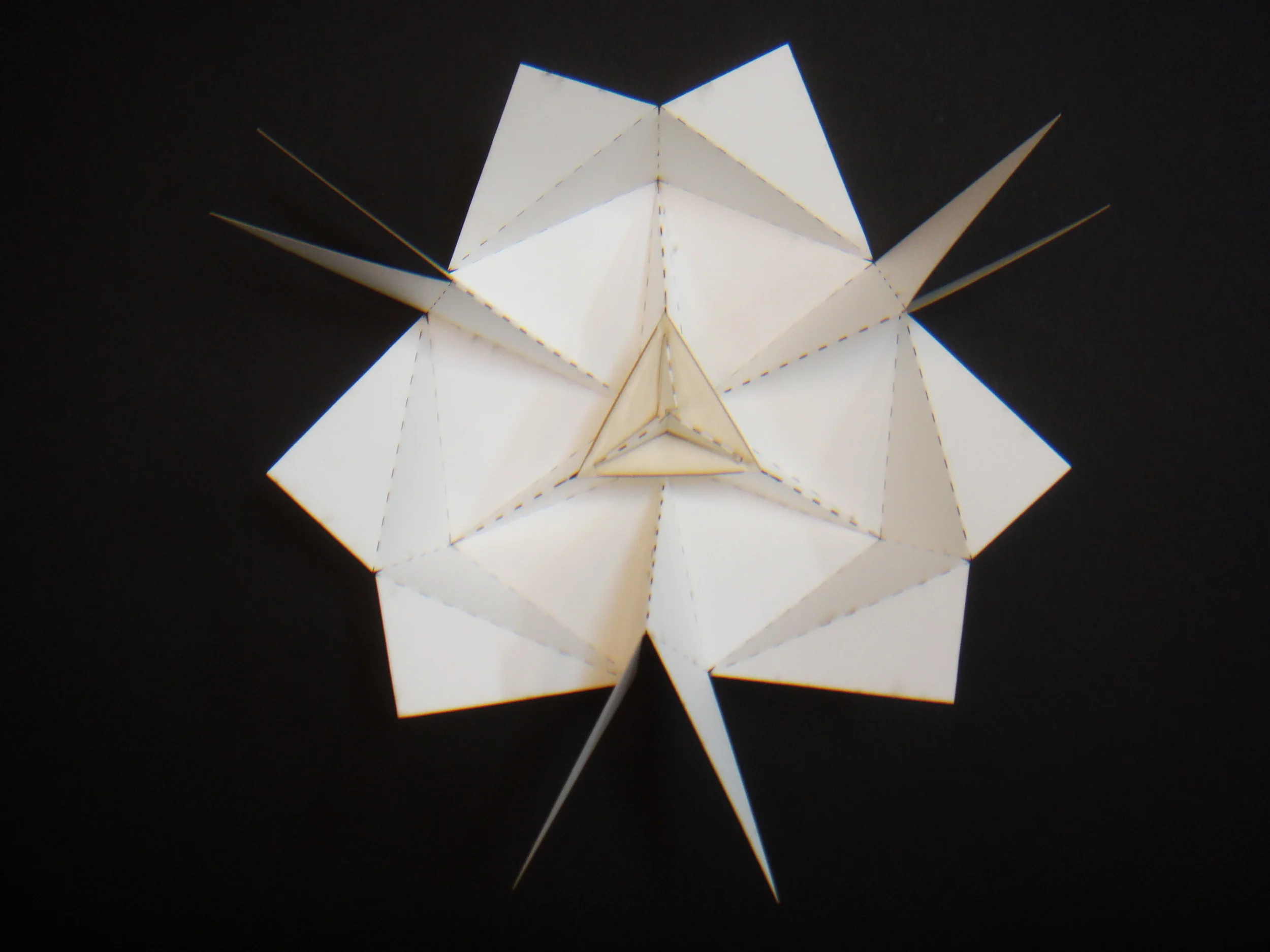

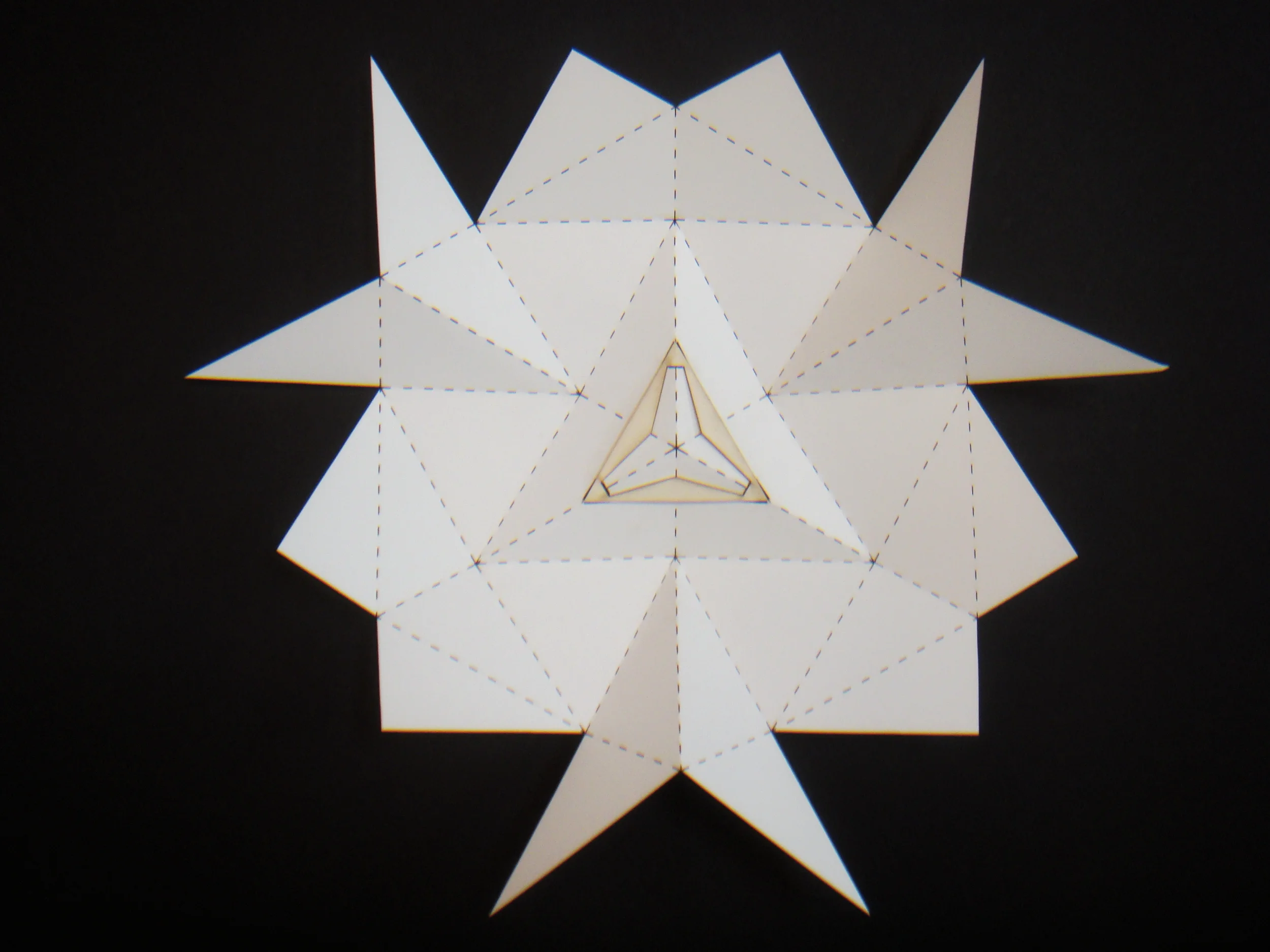

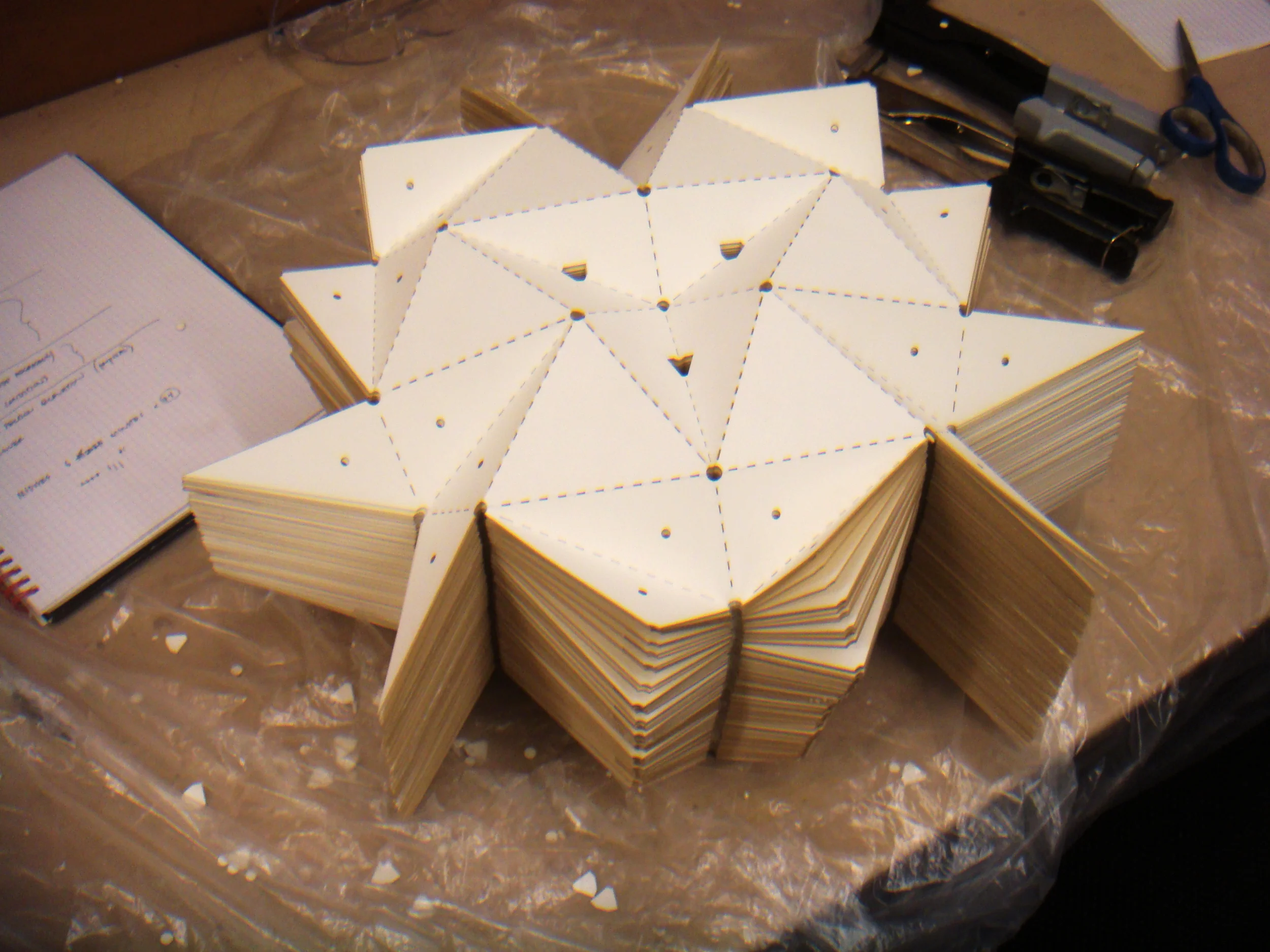

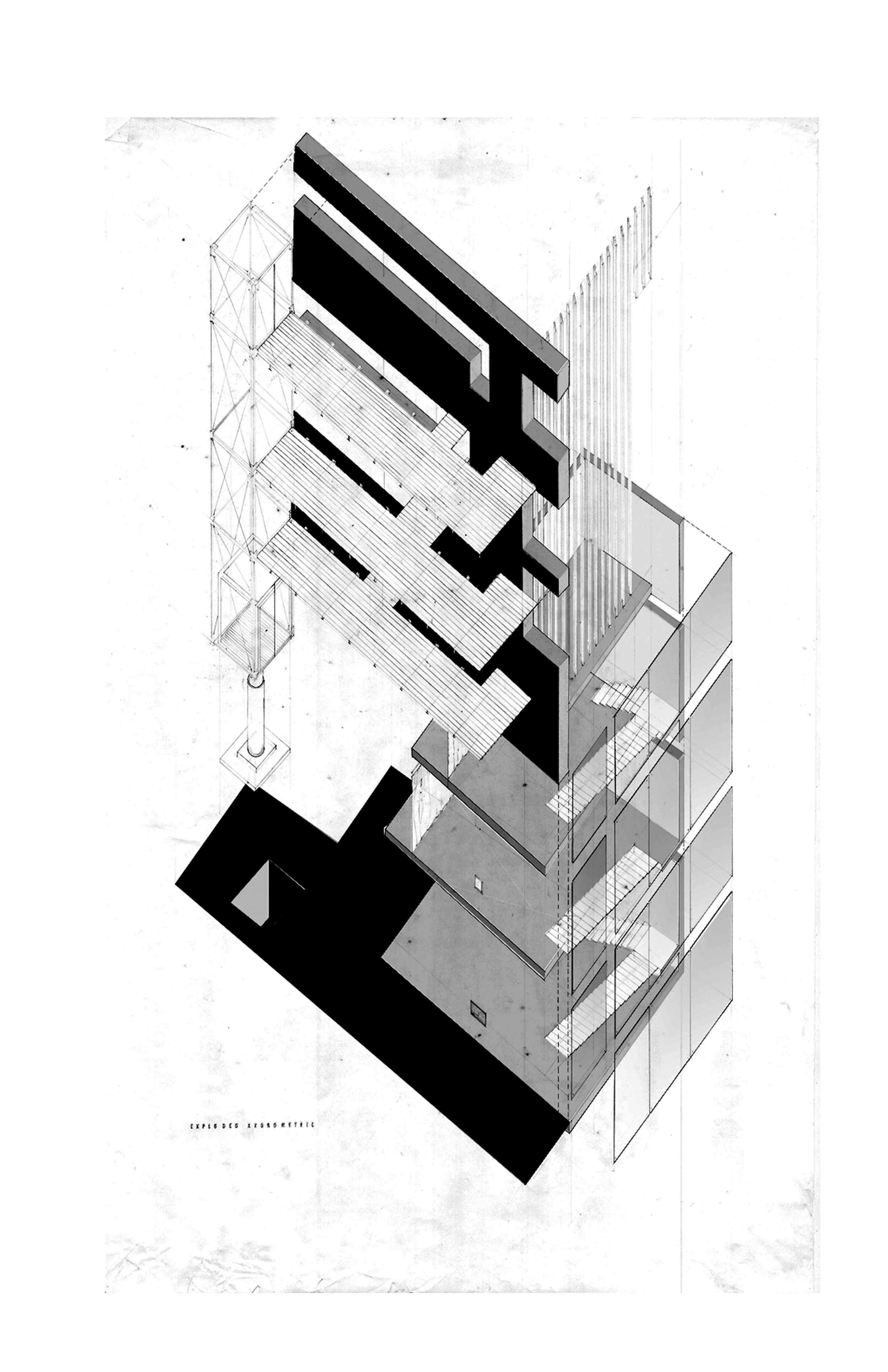

The facility of the school floats as a long bar above the market layer of the street and connects vertically through a series of large lift plates to the underground program of the library, archive and auditorium, the train platform, and the mechanical and material storage below. These large vertical lifts attempt to intervene with the horizontal program depending on where they are engaged. In the instance of the largest lift, a gallery can exist in the library, school, or roof park depending on the particular purpose of the event leaving in its absence a huge atrium for cross visual connections. At a smaller scale, a classroom can exist as a meeting space on the facility floor, as an isolated room for direct lecture, a public seminar space at the mezzanine level, or a kiosk at the roof park. At the smallest scale, an individual’s personal archive space raises and lowers from the floor allowing for a variety of work clusters to form, or in the extreme, to create a completely open hall.

Each mechanism carries a dual function. When they are all working in network, the building is intended to absorb and filter relevant information, engaging both internal and external review, then package and distribute the idea, product, or service to a broad reaching network through public transit routes. By participating with the cycles of already established by existing infrastructure, the school for architecture no longer exists in isolation but instead acts as an urban think tank for the public environment, taking pulse, if you will.

This presentation presents the project as a series of scenarios understanding that no one image can convey the entire process. Some are specific to the time it takes for a pedestrian to exit the train, a day in the life of a student, a year in the life of a project, a seasonal change in the market, or even a the projected life span of the building itself. This is not a heroic form, but instead a tightly packed machine that serves the city as a Design Institute that elicits participation. Through this creative and critical participation in the public, “architecture” education can once again align itself as an incubator of culture or a even a facility for environmental relief.

Harking back to Walter Gropius in a “Design and Industry” c. 1950 “If mechanization were an end in itself, it would be an unmitigated calamity, robbing life of half its fullness and a variety by stunting man and women into sub-human, robot-like automatons. But in the last resort mechanization can have only one object: to abolish the individual’s physical toil of providing himself with the necessities of existence in order that hand and brain may be set free for some higher order of activity.”

SPRING 2011 | MIT

INSTRUCTOR:

Cristina Perreno